Priorty Actions For The Future

Conservation of watersheds

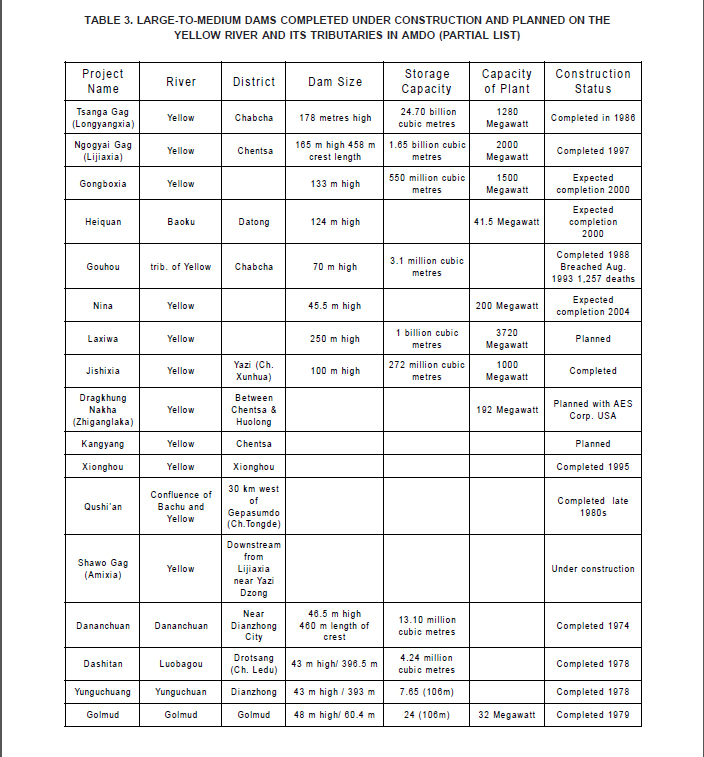

Much of the development in Tibet described above reveals a pattern focusing mainly on natural resource extraction. Mining and deforestation are the most obvious examples of this; the utilisation of rivers for hydropower and irrigation is another facet of the same focus. The Upper Yellow River is primarily utilised for the generation of large quantities of power that either facilitates natural resource extraction in Amdo or is transmitted out to burgeoning Chinese cities. Major dams on the Upper Yangtze and its tributaries either transmit power east into China or provide power for logging, mining and other associated industries.

Increasing utilisation of the Yarlung Tsangpo watershed poses many dangers for the sustainability of a fragile ecosystem. The Three Rivers Project, with its programme of agricultural intensification, threatens the Yarlung Tsangpowith pollution from fertilisers and fragmentation from multiple dams and diversions. The associated effects on the soils in the valley will also affect the river in the long run because as soil erosion and salinisation increases so does the salt and silt content of the river. The primary solution for improving the sustainability of water resource utilisation in Tibet — as well as preserving a unique and important watershed ecosystem — is to bring about a fundamental change in the paradigm in which these resources are viewed. The current emphasis in Tibet is on resource extraction. This reduces the value of resources

for their long-term ecological function — a function that is similar to many upper riparian environments which provide stable downstream flows of freshwater and sediment. This does not exclude development in the Tibetan Plateau per se. However, it does exclude development that is primarily focused on over exploitation through resource extraction and commercialisation of agricultural and pastoral production. More importantly, it also excludes development that is primarily planned by a central government operating thousand of kilometres away in Beijing.

Water Conservation

Given the acute shortage of water resources in many industrial regions of China, water conservation, especially upstream on the Tibetan Plateau is vital for the livelihood of millions of people downstream. Zhu Dengquan, Viceminister of Water Resources of China said, “At current rates, a preliminary tackling of the country’s soil and water conservation problem could take as much as 60 to 70 years” (China Daily 1999b). In Tibet irrigation schemes should be planned in consultation and cooperation with local populations and should be scaled down to less ambitious production targets. Local seed varieties that are better adapted to the local environment with less demand for water and artificial fertilisers should be prioritised. Traditional water harvesting techniques should be studied and developed in cooperation with local users. These traditional techniques are often ignored by planners who prefer a top-down centralised know-all approach.

Traditional small-scale techniques of irrigation are bound to be more efficient as the systems are based on the participation of users in all aspects of planning. Conversely, the centralised approach relies on the knowledge of a few “expert” technicians alienating farmers from the process. These techniques involve smaller-scale dams and diversions that do not interfere with the river’s natural course and functions. Preference should be given to methods of rainwater catchment and storage and techniques aimed at minimising water consumption such as drip irrigation should be studied. Crops that are well adapted to local conditions

should be planted. In Nepal, for example, indigenous

irrigation still accounts for three-quarters of irrigated land. (McCully 1996). India has a long tradition of highly-efficient water management which is currently being rediscovered and promoted, due to the failure of many modern centralised techniques. Some of these good and effective practises could be studied and adapted for use in Tibet.

Renewable Energy

Tibet possesses great potential for the generation of power by micro-hydro (up to 100 kW per unit), solar and wind power. As discussed above, the maintenance of small hydro plants in Tibet has been lax and a high proportion have fallen into disrepair. These small power plants can provide villages with a reliable source of electricity with minimal impact on the environment so they should be encouraged rather than left to fall into disrepair. Where micro-hydro is not feasible, solar and wind generation should be considered. A mixture of these techniques should be the focus, rather than relying on any single method, and needs should be calculated on a local scale so that an appropriate solution for each location can be found. The provision of solar powered equipment such as solar ovens and water heaters should be increased so that there is less need for burning wood or manure, which can be put to better use as fertiliser. Due to its high altitude the Tibetan Plateau has one of the highest solar radiation values in the world at 140-190 Kilocalorie per sq. centimetres per year (Zhao 1992). In the Yarlung Tsangpo valley 70-80 per cent of precipitation occurs at night giving the area an extraordinarily high quantity of sunlight. Lhasa averages 3,400 hours of sunshine annually (Zhao 1992). This potential should be fully utilised before resorting to extensive damming of rivers to provide power.

Preventing Pollution

The threat of pollution is one problem that can be easily assessed and resolved, given the will and co-operation of the Chinese government. Control of tailings and wastes from mines could mitigate many of the impacts on watersheds; sewage treatment and control of wastes can also be improved. However, so far mining in Tibet has been carelessly regulated resulting in unnecessary waste production and inefficient use of resources (Lafitte 1998). Other influences on the hydrological regime of Tibet may be farm more difficult to address as they require China to adjust short-term and long-term patterns of economic development. The Chinese government should enforce existing laws and regulations to ensure the safe and efficient operation of mines. As an area that contains the headwaters of so many of Asia’s major rivers, Tibet is the last place on earth where pollution regulations can be relaxed or ignored. Preferably there should be no large scale mining at all in an area in which the highest value should be placed on the ecological function of the upper riparian environment. Surveys should be carried out immediately to discover how much pollution has occurred and to prevent further occurrence.

About 70 per cent of China’s wastewater is dumped into rivers with the Yangtze river receiving 41 per cent of the country’s sewage. The figure is expected to rise in the future. Fifteen out of China’s 27 major rivers are considered to be seriously polluted (Zhu,1990). China planned to increase its spending on controlling pollution from the current 0.8 percent of its GNP to more than one percent at the turn of the century or approximately US $ 17.5 billion (The World Resources Institute 1998). In urban areas, sewage treatment should be developed immediately and industrial pollutants must not be dumped in rivers. Public education campaigns should focus on informing people how to avoid polluting rivers with household wastes and non-biodegradable garbage such as plastics.

Sustainable Development

Tibet, with its huge variety of natural resources and its unique high altitude situation, demands careful location-specific planning to utilise its resources sustainably. Over exploitation in a fragile mountain environment can lead to long-term ecological consequences. The assumption that Tibet can be an endless resource for China’s economic development should be abandoned. With the use of appropriate technologies, Tibet’s resources can be developed in a way that draws upon traditional knowledge of the land and its potential.

International agencies, as well as countries situated downstream from Tibet, should consider targeting any aid to Tibet that encourages in sustainable development and public participation. Continued unsustainable resource stripping — and its associated deleterious effects on waterways — is of grave concern to the billions of people dependent upon these valuable water resources for their livelihood and for the gift of life itself.

comment 0