Introduction of Forestry

IN SUMMER 1998, the worst flooding of the (Drichu) Yangtze River to ravage China since 1954 killed between 3,656 and 10,000 people and left 240 millions affected by its waters. As well as devastating 64 million hectares of farmland and destroying 4.8 million hectares of crops, 5.6 million homes were destroyed and Xinhua (1998h) reported that over 0.5 percentage points were shaved off from the economic growth resulting in a direct financial loss of US$37.5 billion. Epidemics followed due to the spread of sewer and latrine contents. According to China Daily the flood was expected to shift one million citizens’ incomes to below the poverty line of US$75 a year (Pomfret 1998b; Tibetan Review 1998b).

The Chinese government was slow to confess that a major cause of the Yangtze flood was extensive deforestation at the river’s source, which lies deep inside the Tibetan provinces of Amdo and Kham. Chinese statistics state that the Yangtze then peaked at approximately 55,000 cubic metres per second, a rate it had exceeded 23 times since 1949. It has been estimated that the Yangtze now discharges 500 million tons of silt a year into the East China Sea, a volume equivalent to the total discharge of the Nile, Amazon and Mississippi Rivers combined (Pomfret 1998b; He 1991).

Traditional Conservation

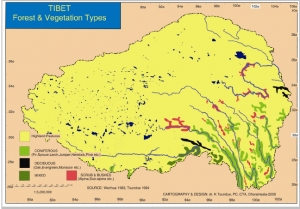

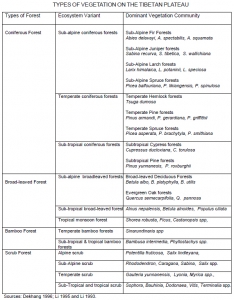

Situated at the centre of the Asian continent, the Tibetan Plateau not only contains the world’s highest mountains and a vast arid plateau, but also fertile river valleys and ancient forests. The major forested areas on the Tibetan Plateau are in the south (Dram, Kyirong, Pema Koe, Kongpo, Nyingtri, Tawu, Metog and Monyul), the east (Chamdo, Drayab, Zogong, Kandze, Potramo, Dartsedo, Nyarong and Ngaba), and the southeast (Dechen, Balung, Gyalthang, Mili, Lithang, Zayul, Markham and Dzogang).

These forested regions are primarily located on steep isolated slopes and prior to 1950 covered over 25.2 million hectares representing about nine per cent of the region (DIIR 1992). The plateau possesses one of the oldest forest reserves in Central Asia and a wealth of over 100,000 species of higher plants, 532 species of birds, and many rare wild animals such as giant panda, golden monkey, takin, and whitelipped deer (DIIR 1998a). These forests provide a variety of fruits, nuts and vegetables, including apple, pear, orange, banana and walnut. Given the remote and restricted conditions of the plateau, several of its botanical species have yet to be adequately studied and classified.

Tibet’s small population lived primarily on sheep- and yak-herding and barley cultivation, leaving fields fallow for long periods which maintained fertility and helped prevent leaching and erosion. Wildlife was protected in accordance with Buddhist principles, while timber was harvested on a controlled and selective basis (Winkler 1996).

Tibet’s small population lived primarily on sheep- and yak-herding and barley cultivation, leaving fields fallow for long periods which maintained fertility and helped prevent leaching and erosion. Wildlife was protected in accordance with Buddhist principles, while timber was harvested on a controlled and selective basis (Winkler 1996).

There are over 2,000 plants used in Tibetan and allopathic medicines which can be collected in the Tibetan Plateau. Tibet’s ancient medical system is highly respected throughout Central Asia and has a remarkable record of success in healing (Burang 1974).In direct contrast to the standpoint of allopathy, Tibetan medicine mirrors the principles that operate in nature, preferring a slow and gentle treatment that places great emphasis on natural remedies, treating humans and each medicine as an integral part of the environment (Badmayew et al 1982).

Deforestation in China’s History

Compared with the Tibetans, China’s inhabitants have suffered a long history of ecological crisis and ancient documents show that the deterioration of Chinese forests has been taking place over thousands of years. The pace of deforestation accelerated ever since the 14th century, setting the precedent for a destruction that continues today. Starting from China’s Ming period (1368-1644), all the forests in the central region of the Huang River valley, as well asthe Xiang River valley were seriously denuded (Edmonds 1994).

The forest cover in China amounts to only 0.11 hectares per capita which is significantly below the world average of 0.77 hectares per capita. China is also the third largest consumer of timber in the world and faces an amplified imbalance between demand and supply for wood products. The present annual consumption level of approximately 300 million cubic metres of round wood exceeds the combined annual forest growth increment and total imports by about 50 million cubic metres per year. As a result, an estimated 500,000 hectares of forest area is lost each year; this is equivalent to 0.5 per cent of total forest area (Ministry of Forests 1997).

Tibet’s Shrinking Forests

China now sees the Tibetan Plateau as its largest forest zone as industrial timber extraction penetrates deeper into Tibet’s borders. Some 70 state logging enterprises have cut a total amount of 120 million cubic metres of wood from the forests of eastern Kham (Sichuan), generating over 2 billion yuan (US$ 241 million) in taxes and profits between 1949 to 1998 (TIN 1998d). It is said that forest exploitation in western Sichuan is 2.3 times more than forest productivity (ICIMOD 1986). According to Tenzin Palbar, who escaped from Tibet into India in 1987, in the Ngaba Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture from 1955-1991 the Chinese government extracted 50.17 million cubic metre of Tibetan timber, which is worth US$ 3.1 billion in Tibet itself when calculated at the average price of 50 yuan per cubic metre.

In this region there were 340 million cubic metres of forest in 1950 which reduced to 180 million cubic metres in 1992, of which only 34 million cubic metres could be used. Therefore, Ngaba lost 47 per cent of its forest cover between 1950 to 1992 alone (TIN 1999a). Income from the forestry industry is the main source of cash income in many of the poorest counties in Sichuan.

In the region of Kham absorbed into Sichuan, forest cover decreased from 30 per cent in the 1950s to 14 per cent in the 1980s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s the momentum has continued (Li 1993). In Ngaba (Ch:Aba) and the Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture forest cover shrank from 29.5 per cent in the 1950s to 14 per

cent in the 1980s (Yang 1986). This has left eight out of 11 forest factories in Ngaba district with exhausted resources. Similarly, in the Kandze district, five of seven forest reserves have been depleted (Zhao 1992). Reports from the World Watch Institute estimate the heavily-forested area from the Tibetan Plateau to the Yangtze River basin has lost 85 per cent of its original forest cover (Brown and Halweil 1998).

Forest herbs have immense value in China and Chinese timber factories in Tibet claim to have culled up to eight million cubic metres of herbs, with a value of US$17.2 million (Dekhang 1996). This confirms that exploitation of Tibetan forests is not restricted to timber alone.

Treasure and Treasury

Recognition of the “natural” world’s interdependent values is fundamental to creating a healthy relationship with one’s environment. When forests are understood only in a utilitarian context many other values are disregarded and consequently sacrificed and harmed. It is undeniable that timber resources extracted from forests are indispensable to human life. Additionally, a forest contains abundant plants and animals, complex stratified structures, many biological products and immense capabilities to exchange substance and energy, which play important roles in maintaining the life-support system of this planet. Forests are not only a treasure but also a treasury of plant and animal resources. In brief, the concept of “forest” means not merely timber, but also a simultaneous consideration of intrinsic, ecological, social and economic values.

Fuelwood and Land Cultivation

It has been suggested that the traditional use of forests for fuelwood by the inhabitants of the Tibetan Plateau is a major contributing factor to deforestation of the area. However, upon closer examination it becomes clear that despite the large demand for fuelwood, traditionally Tibet’s population was small and most fuel was derived from shrubs, branches and predominantly agricultural residues such as dung (DIIR 1992). This fact was also reconfirmed in December 1998 by a majority of the newly-arrived Tibetan refugees interviewed in Dharamsala. Furthermore, in Lhasa fuelwood is now sold at a price per cubic metre that exceeds the average annual per capita income (Richardson 1990). Hence, the traditional use of forests for fuelwood on the Tibetan Plateau accounts for a negligible part of the pressure onforest cover.

As illustrated by Winkler’s research, Tibetan traditions were not completely without effect and have slowly altered the environment over several millennia. One example is the reduction of forest cover through grazing. “Full utilisation of the south-facing slopes for winter grazing enables herders to keep their store of winter fodder which is a time- and energy-consuming necessity in any environment with harsh winters to an absolute minimum” (Winkler 1998). However, unlike the consequences of commercial timber extraction and uncontrolled resource liquidation, the impact of the past was not a short-sighted destruction of resources, but rather a logical consequence of developing various regions of Tibet as grazing land. But in today’s Tibet, as in many

places around the earth, processes of land alteration that evolved over thousands of years can now happen within decades or even years.

Faulty Forest Enforcement

While deforestation on the Tibetan Plateau is a complex issue and its causes are difficult to isolate, Tibetan, Chinese and foreign researchers maintain that the dwindling forest cover is primarily caused by poor forest management. Forest management in this context is an inclusive term that refers to human-created changes in environmental conditions ranging from random timber poaching and various inefficiencies to high-yield industrial logging. A host of administrative dilemmas face China in its forest practices. This predicament is embedded in faulty enforcement rather than in a crisis of insufficient forest laws. For example, Article 25 of the (Forestry Law(s) of the People’s Republic of China 1985) further states that: “The state, acting on the principle that consumption of the timber forest should be lower than its growth, imposes strict control on the annual forest cut” (Richardson 1990). Recent government planning is targeting reforestation with the intention of increasing the forested area to a level of self-sufficiency. Unfortunately, there are inherent deficiencies in the Chinese system that create gaps between policy and practice and nullify optimistic goals, which in turn perpetuates high deforestation rates.

comment 0