Himalayan ‘drop after Nepal quake’

By Navin Singh Khadka

Environment reporter, BBC World Service

The height of a swathe of the Himalayas has dropped by around one metre as a result of the devastating Nepal earthquake, scientists say. But they add that the drop will roughly be balanced by slow uplift due to tectonic activity.

And they have yet to analyse satellite images of the region in which the most famous Himalayan peak Everest is located. However, there continues to be debate over exactly how tall Everest is.

“The primary stretch that had its height dropped is a 80-100km stretch of the Langtang Himal (to the northwest of the capital, Kathmandu),” said Richard Briggs, a research geologist with the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

The Langtang range is the region where many locals and trekkers are still missing, presumed dead, after the avalanches and landslides that were triggered by the 7.8 magnitude earthquake on 25 April.

Scientists believe the height of a handful of other Himalayan peaks, including the Ganesh Himal to the west of the Langtang range, may also have dropped.

The satellite images they have analysed so far have focused on central Nepal, which was the hardest hit by the quake. Everest is to the east of this main shaking zone.

Scientists say whether or not the world’s highest peak saw a change in its height by few centimetres will have to be further confirmed by ground survey and GPS or an airborne mission.

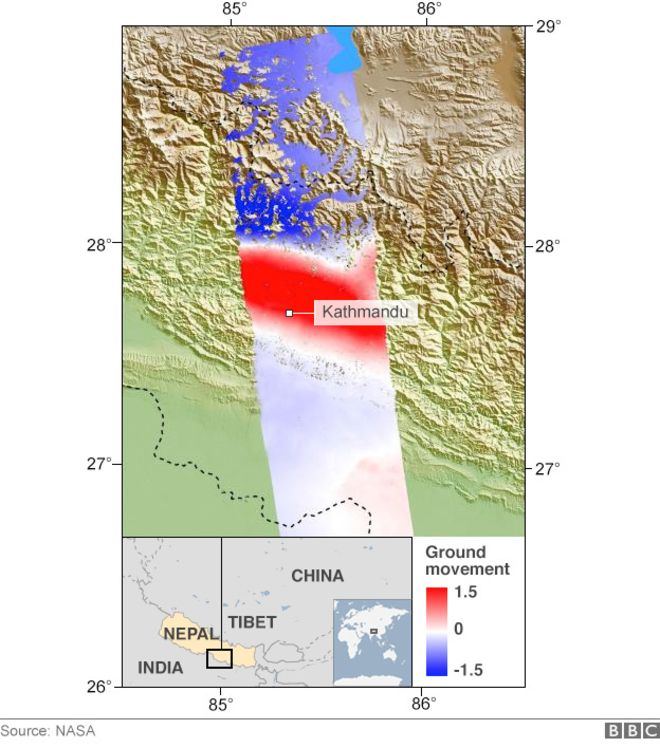

“But what we see in the data that we evaluated further away from the plate boundary, to the north of the capital Kathmandu, is a clearly identifiable region with subsidence of up to 1.5m,” says Christian Minet, a geologist with the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), which processed the Nepal earthquake data sent by the Sentinel-1a satellite.

Before and after images

Scientists with DLR’s Earth Observation Centre of compared two separate images of the same region sent by the satellite, before and after the quake.

“The positive value we have received (from the satellite image) after the quake means the area (the mountains in and around the Langtang region) is further away from the satellite and it is lower now,” said Mr Minet.

“But with this result we cannot say that a specific mountain is one-point-something-metres lower; it is the general area that we can assess.”

He said the satellite images showed the area of the mountain range had dropped by 0.7m-1.5m.

The study has also found that areas including the capital, Kathmandu, to the south of the Himalayan mountains have been uplifted by the quake.

“The negative value we have received from the acquisitions of the before and after earthquake images means that some areas (Kathmandu and its surroundings) are now closer to the satellite, and that means they have seen an uplift,” says Mr Minet.

Scientists say the drop and the uplift are normal geological behaviour during an earthquake of this scale.

Head-on collision

“The fault underneath Kathmandu has slipped and it’s moved the overriding part of the crust to the south towards the southern end of the part that squashes the crust; and to the northern end it stretches it,” says Tim Wright, professor of satellite geodesy at the University of Leeds.

“From where it is squashed, which is more or less underneath Kathmandu, we get uplift. And where it stretches, which is in the high mountains to the north of Kathmandu in this case, we get subsidence.

“The biggest amount of slip on the fault was actually just north of Kathmandu, so it’s the mountains north of Kathmandu that have subsided the most in this particular case.”

Normally, the Himalayas are on the rise because of the collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates.

But during major earthquakes the process gets reversed, experts say.

“Between earthquake events, Nepal is being squashed and the part (including Kathmandu) nearest the big fault underneath it is being dragged down by the Indian plate, and [areas] further back are being lifted up as you imagine squashing something is going to push things up,” says Prof Wright.

“Now, during the earthquake itself what happens is the opposite. The part that was dragged down because it was stuck at the fault – that slips freely and rebounds up, and the part that was being squashed upwards drops down.”

Authorities in Nepal say they are yet to assess the impacts of the earthquake on the Himalayas as they are still occupied with rescue and rehabilitation after the devastating earthquake.

Source: BBC

comment 0