Introduction to Water Resources of Tibet

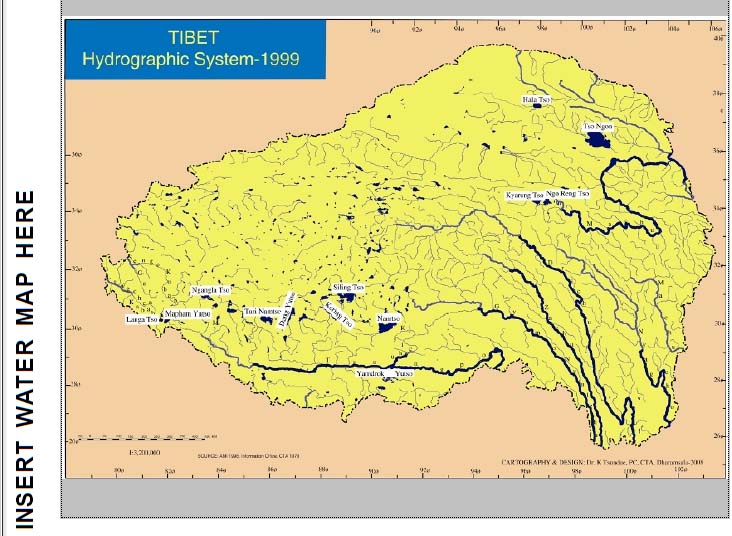

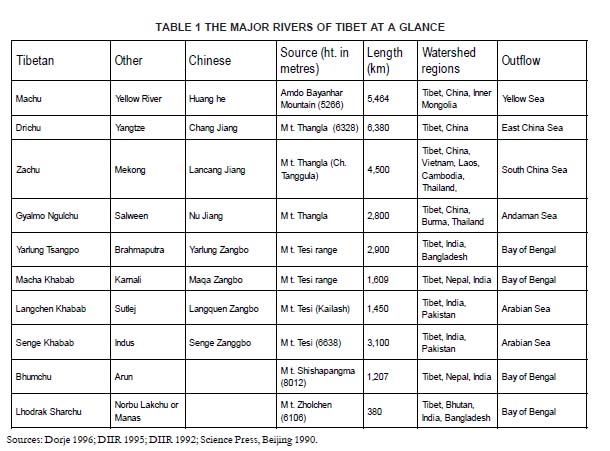

THE MOUNTAINS of Tibet constitute the headwaters of many of Asia’s major rivers. Tibet’s high altitude, huge landmass and vast glaciers endows it with the greatest river system in the world. Tibet’s rivers flow into the most populous regions of the world, supplying fresh water to a significant proportion of Asia’s population (see Table 1) Tibetan rivers are distinguished by their high silt loads resulting from the largely desert landscape from which they originate.

In the Zachu (Mekong), Gyalmo Ngulchu (Salween) and Drichu(Yangtze) watersheds, as well as the eastern reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo, deforestation is steadily increasing these high silt loads. Net hydro-logical flows in Tibet total 627 cubic km per year. This comprises roughly six per cent of Asia’s annual runoff and 34 per cent of India’s total river water resources. Historically, negligible utilisation rates in Tibet meant that nearly all of this water was transferred to countries in downstream basins including India, Nepal, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan, Vietnam, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. Today, hydrological transfers from Tibet to other countries total 577 cubic km from a gross basin area of 1.1 million sq. km.

This excludes internal and landlocked rivers. Transnational flow thus accounts for 92 per cent of net hydro-logical flows. The availability of fresh water in Tibet — 104,500 cubic metres per year — ranks fourth in the world after Iceland, New Zealand and Canada, and is 40,000 times higher than in China. Given the low precipitation in Tibet, a higher proportion of river flows originate from glaciers which have a total area of 42,946 sq. km and groundwater sources. Perennial sources like these result in what are called stable or base flows. Because they are independent of seasonal precipitation patterns they are an important factor in sustaining hydro-logical regimes (DIIR 1992).

The quantity of water flowing from the plateau, and the steep gradients, mean the hydro power potential of Tibet’s rivers is among the highest in the world. Over two thirds of China’s hydro power potential is located in, or directly surrounding, Tibet. The hydro power potential of this area has been calculated at 1305 TWh (Cheng 1994). The Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo in Southeast Tibet is estimated to have the largest hydro power potential of any place on earth at 70,000MW (Verghese 1990). The gorge where this potential exists has become the focus of recent exploratory expeditions. Currently, the exploitation of hydro power resources in Tibet is mainly concentrated on the Upper Drichu (Yangtze) and its major tributaries the Yalong and Dadu Rivers in Kham.

The Upper Machu (Yellow River) in Amdo is also the focus of large scale hydro power exploitation. Tibet is endowed with more than 2,000 natural lakes. The major ones include Tso Ngonpo (Kokonor), Nam Tso, Yamdrok Tso — the largest fresh water lake in the North Himalaya — Mapham Tso and Panggong Tso. The largest lake in Tibet is Tso Ngonpo, which has an area of 4,460 sq. km. The combined area of Tibet’s lakes is over 35,000 sq.km

accounting for about 1.5 per cent of the country’s total surface area (DIIR 1992). The catchment area ecology of most of the lakes is relatively unknown and utilization of their waters has remained low until recent times. Many of these lakes have been receding slowly due to natural processes for thousands of years. According to Chinese surveys, there are 71 species and sub-species of fish in the ‘Tibet Autonomous Region’ (‘TAR’).

This constitutes 63 per cent of the species and sub-species on the entire Tibetan Plateau. Among these are various species of: Schizothoracinae, Nemacheilinae and Sissoridae (Zhang 1997). There were no cases of Tibetan rivers being diverted, polluted or extensively fished before 1949. A small hydro power station was built in 1928 in the Togde Gully on the Kyichu with an installed capacity of 92 kw (Yan 1998).

Diversions for irrigation were also minimal. In this period, Tibet’s agriculture was dependent on monsoon rains and small-scale river diversions organised on a village basis. These would have had a negligible impact on the flows of Tibet’s rivers. The absence of any modern industry at this time, and the low population density, meant that it was unlikely that wastes entering Tibet’s rivers caused any significant pollution. For devout Tibetan Buddhists eating fish is a sacrilege. There is a saying: “Because a fish is without a tongue, killing is unforgivable” (Duncan 1961).

Fish were not an important part of the Tibetan diet. Therefore, few people engaged themselves in fishing. The fishing activity around Yamdrok Tso in southern Tibet was regulated by the central government in Lhasa as the lake is of great spiritual significance. The Kashag (Cabinet of the Tibetan Government) regulated the size of fishing net holes so that young fish and other non-edible creatures were protected (Tsering 1996). Therefore the exploitation of fish resources prior to 1949 was minimal and so where harvests were cpmsequently.

WATER FOR THE MILLIONS

As mentioned above, rivers originating in Tibet flow into various regions in Asia. In some cases the distance traversed by these rivers through Tibet is short, while for many of them Tibetan terrain constitutes a large proportion of the rivers’ total length and contributes largely to the rivers’ perennial flow. Since Asia is dominated by monsoon patterns of rainfall, bringing rain for only a few months (usually three months) of the year, the perennial flow of its rivers relies upon the constant flux of glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau. Tibet’s high altitude causes extreme diurnal variation in temperature, so that every day, winter or summer, glaciers can partially melt and refreeze. This daily snow melt feeds the river systems.

From Tibet’s Rivers Flows Asia’s Survival

For 1,600 km of its total 4,500 km length, the Mekong traverses through Tibetan territory (Lafitte 1996). Beginning in Amdo, the Mekong passes through the eastern side of Tibet near Sangang and Chamdo and flows near the Tibetan town Jol and then Balang to the Chinese town Lajing in Yunnan Province. It then continues in a south southeasterly direction through Yunnan and on into Southeast Asia. After leaving China, the Mekong flows through Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

The Salween begins in Thangla Mt. (Ch. Tanggula) in Tibet and flows east towards the Mekong. It then travels in an almost parallel gorge just west of the Mekong in the

Khawakarpo Mountains. Once in Kham, the two river valleys diverge and the Salween heads southwest into Burma, where it becomes the country’s primary river.

The two great rivers of China, the Yangtze and the Yellow, originate high up on the plateau in Amdo. The Yellow River travels northeast through Amdo before entering the Loess Plateau and the North China Plain. This region of China supports 550 million people and two thirds of the country’s cropland. However, the watershed only supplies one fifth of the country’s water. The Yangtze watershed and the region to its south supports slightly more people (700 million), accounting for four fifths of China’s total water yet only one third of the country’s cropland (Brown & Halweil 1998).

The imbalance of water resources to cropland between these two major watersheds of China is emerging as one of the Beijing’s biggest ecological problems. As groundwater and river water is becoming exhausted in the north, Chinese engineers are contemplating massive inter-basin water transfer projects. In the southwest of Tibet, four major rivers originate around Mt. Tesi (Kailash). One is the Yarlung Tsangpo which travels for over 2,200 km within Tibet.

Its easterly course skirts north of the Himalayan divide before turning sharply south into the plains of Arunachal Pradesh, India, where it becomes known as the Brahmaputra. After flowing through the Assam Plain in India, the Yarlung Tsangpo enters Bangladesh to irrigate the fields of the country’s 128 million people, before joining the Ganges and the Meghna to form the great delta of northeastern India known as the Sunderbans. The Senge Khabab (Indus) has its source north of Tesi mountains (Kailash).

It then passes west into Ladakh as the Senge Tsangpo and then to Kashmir and continues to become Pakistan’s principle river. The Langchen Khabab (Sutlej) begins west of Tesi mountains, crossing the Himalayas into Himachal Pradesh in northwest India, passing through the Punjab region before joining the Indus in Pakistan. The Macha Khabab (Karnali) originates from Mt. Tesi Range (Kailash Range), crosses the Himalayas into western Nepal and then into India where it joins the River Ganges. Fertile River Valleys Every year the major rivers flowing out of Tibet flood when the spring sun melts the winters’ snow and then again when the monsoon rains arrive — mostly between July and September.

At times these floods are severe, often wreaking havoc downstream as they did in China and Bangladesh in 1998 and 1999. Nevertheless, a regular annual flood can be a beneficial function of a healthy river. As these rivers cascade down into the foothills and plains of Asia they bring with them more than just water. The silt loads of Tibet’s rivers deposit millions of tons of silt and sediment to create fertile river valleys and flood plains in the downstream regions in Asia. This is the key to maintaining the viability of downstream ecosystems.

The fertile river valleys of Brahmaputra, Yellow and Mekong are cases in point. As the floods recede they leave behind silt which replenishes the topsoil with vital trace elements such as silica and iron. This sedimentation process also maintains the deltas of major rivers. The annual flood also facilitates the breeding of freshwater fish. While the floods are at their peak, fish swim into the shallows and lay their eggs in still waters where they can develop without disturbance. As the floodwaters recede, the hatchlings find their way into the main streams.

These benefits are not always appreciated by agro-scientists and developers and, perhaps not surprisingly, by those affected by the floods. Catastrophic floods appear to be becoming more regular and more severe. This is a possible consequence of the interference in hydrological systems, climate change and continuing deforestation. It is becoming increasingly clear that rivers have more ecological functions than just the provision of water. The interaction of flood plains and rivers is one such vital function. The Tibetan Plateau — with its weather patterns, hydrological system, glacial conditions, forest, and soil functions — has an essential influence over Asia (with high population densities) and which also provide sustenance to some of the world’s most productive agricultural zones.

Source: Tibet 2000 Environment and Development Issues, Environment and Development Desk, DIIR

comment 0